in Life/Philosophy — by Farooque Chowdhury — September 28, 2019

[On Bhagat Singh’s 112th birth anniversary, this article, 1st part of a series, introduces Bhagat Singh Reader by Professor Chaman Lal]

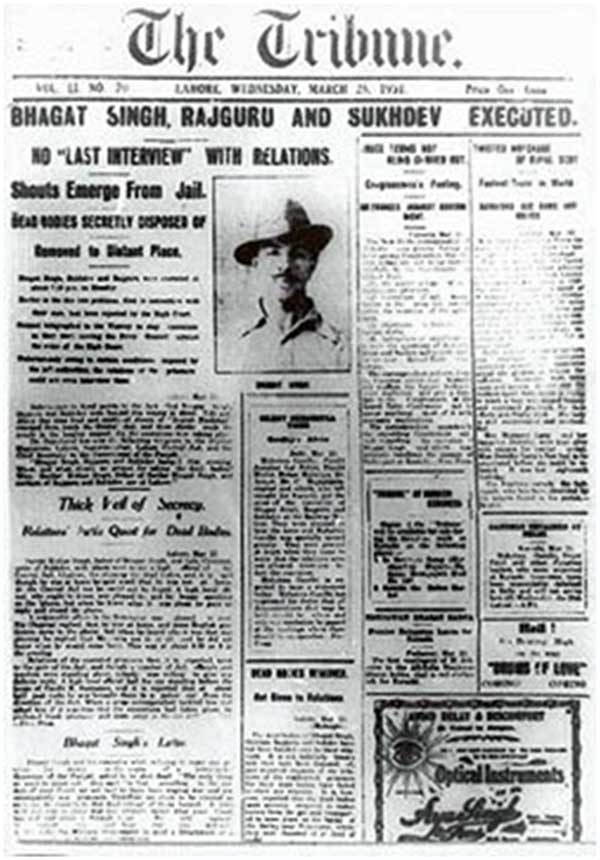

The Tribune’s lead informs execution of Bhagat Singh, and Rajguru and Sukhdev, his comrades.

Bhagat Singh. The revolutionary. The visionary. The ideological warrior. The organizer. The voice of the exploited.

The perspective was this sub-continent, brutalized, tormented, muzzled, appropriated and plundered by the imperialist United Kingdom with the so-called civilized face of an unashamed barbaric power.

People in this sub-continent, Bangladesh-India-Pakistan, remember the fighting soul with love and reverence. People in this sub-continent recollect lessons the revolutionary imparted, and the lessons the revolutionary’s actions created. Summarization of these two types of lessons is the need in people’s struggle whoever strives to organize wherever – from teeming urban centers to industrial and rural areas – in whatever form.

On the revolutionary’s 112th birth anniversary, a 638-page book – The Bhagat Singh Reader – by Professor Chaman Lal is worth looking into as the book presents a lot of information related to the revolutionary. Chaman Lal – a revolutionary, young in terms of spirit but turned aged by time-uncheckable – is one of the foremost veteran political activists in today’s Bangladesh-India-Pakistan striving to spread the message of Bhagat Singh, born on September 28, 1907 at village Chak number 105 at Lyallpur (now, Pakistan has renamed the place at Faisalabad). The British colonial rulers executed Bhagat Singh on March 23, 1931 in Lahore (today a major city in Pakistan). Pattabhi Sitaramayya, historian, activist and member of the Congress party, evaluated: Bhagat Singh’s popularity soared so high that it was equal to Mahatma Gandhi’s popularity.

Chaman Lal, the retired professor and former chairperson of the Centre of Indian Languages at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, writes his first encounter with Bhagat Singh in the “Note on compilation and editing” of the book published by HarperCollins Publishers India (Noida, Uttar Pradesh) in 2019. It’s a part of a story of Chaman Lal’s revolutionary activism in yesteryears:

My interest in Bhagat Singh and other Indian revolutionaries began even before I was twenty years old. My interest was first aroused by Manmath Nath Gupta, a convicted revolutionary in the Kakori case, who later turned into a historian of the Indian revolutionary movement during the freedom struggle and wrote the Hindi book Bharat Ke Krantikari (Revolutionaries of India).”

Chaman Lal translated the book into Punjabi in the early-‘70s. Revolutionary movements and life of revolutionaries were always in Professor Lal’s mind. He edited Bhagat Singh aur Unke Sathiyon ke Dastavez, which was published in 1986. It was a book on Bhagat Singh and his comrades. He specified his interest, and began searching documents related to Bhagat Singh.

He found: Bhagat Singh, as he writes, “the most organized in his thinking about the revolution and the means to achieve it. Bhagat Singh went beyond the tradition of the early revolutionaries and gave an ideological direction to the whole movement, which had been missing earlier.”

Prof. Lal, thus, brings an aspect – “ideological direction” – to the notice of readers. A section of today’s firebrand activists misses this ideological direction. Otherwise, this section wouldn’t have missed questions of class, mobilizing the masses, and imperialist design and interference in this sub-continent while getting busy with slogan mongering and showmanship; this section wouldn’t have embraced one faction of ultra-right forces in the name of opposing another faction of the same forces, and wouldn’t have ignored the question of imperialism. This section wouldn’t have chided masses of people for the people’s “stupidity and timidity” while they make near-zero ideological work among the people had the section any ideological direction.

Chaman Lal writes:

“Bhagat Sigh realized that the goal of the Indian revolution should be a socialist revolution, which aims at ending not just colonial rule but class rule as well.”

Professor Lal’s angle of viewing Bhagat Singh is now clear, and specific: “Ending class rule”. The class rule question is also missed by a section today although ending class rule is the only way of eliminating all forms of apartheid, repression, segregation, exploitation. So, there’s Lenin in Bhagat Singh’s political ideas. “On 21st January, 1930, Bhagat Singh and his comrades read out a telegram in the British Court that they wanted to send to Russia. The telegram sent ‘REVOLUTIONARY GREETINGS TO THE GREAT LENIN’. [….] When, finally, Bhagat Singh was summoned to be hanged, he was reading Lenin.” (Amaresh Mishra, “Why Lenin is special to India?”, The Citizen, March 8, 2018)

Chaman Lal draws a demarcating line while discussing Bhagat Singh:

“Before Bhagat Singh, the revolutionary movement was the study of the bravery, fearlessness, and patriotism of the revolutionaries. With Bhagat Singh, it took an entirely different turn and became a study of ideas of the revolutionaries, and not just about their brave actions.”

The 8-page “Note …” by Chaman Lal carries a lot of facts on the great revolutionary. A few of those include: (1) At the age of 16, the revolutionary penned his first essay. (2) His first published essay was “The problems of language and script in Punjab”. (3) Most of his essays are found in print form, and almost all are attributed to fictitious names. (4) The only documents found in Bhagat Singh’s handwriting are either letters or the Jail Notebook.

The book in five sections and appendices begins with letters and telegrams. The section with letters include letters from school, college, revolutionary life, political and personal letters, and telegrams, in separate sub-sections, from jail, and letters to the colonial administration/judiciary from jail. The list cited here is enough to tell that the book is useful for a study of Bhagat Singh. At the same time, it tells at least a part of the “civilized” rule of the barbaric colonial masters.

Similarly, the appendices include (1) Manifesto drafted in consultation with Bhagat Singh, (2) Manifesto of Naujawan Bharat Sabha, (3) Manifesto of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, (4) Language-wise details of Bhagat Singh’s writings, (5) genealogy, (6) ordinance by British viceroy, (7) Lahore Conspiracy Case judgement, (8) Privy Council judgement, (9) a list of newly-found materials.

These two sections are enough to comprehend the professor’s labor with the revolutionary. Other sections confirm the claim made here – labor, intensive labor with the subject of study.

The editor’s “Note …” tells, known to many, but unknown to many of today’s new comers in people’s politics, a few more facts, which echo spirit and commitment of the revolutionaries of the colonial time:

(1) Bhagat Singh joined revolutionary movement at the age of 16 in 1923 and had less than seven years to achieve the goals of the revolution he dreamed.

(2) Bhagat Singh not only carried out political revolutionary acts, but also wrote prolifically.

(3) He wrote in four languages – Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi and English.

(4) He had a good command over Sanskrit, and understood Baanglaa very well.

(5) Bahagat Singh could recite Tagore’s and Nazrul’s poems in Baanglaa fluently.

(6) He began learning Persian.

(7) He wrote 130 documents in seven years, and the documents spanned nearly 400 pages.

(8) Bhagat Singh wrote his first political letter to his father in Urdu.

(9) He was most comfortable in writing Urdu, as it appears from his letters of personal nature to his family members.

(10) He had a good command over Hindi.

(11) He studied Sanskrit in school.

(12) Two of his essays – “Vishwa Prem” (“Universal Love”) and “Yuvak” (“Youth”) – published in Kolkata-based Hindi journal Matwala were written in Sandkritized Hindi.

(13) All of his writings from jail, between April 8, 1929 and March 22, 1931, are in English.

(14) Even though Bhagat Singh had not studied beyond F.A. (Faculty of Arts) Program of at college level he had a powerful command over English language “so much so that at a court-hearing in the Delhi Bombing Case, the judge told Bhagat Singh’s counsel, Asaf Ali, that the judge suspected it was the counsel and not Bhagat Singh who was drafting the ‘statements’ by the accused.” Historian V N Datta has even speculated in his book Gandhi and Bhagat Singh that perhaps Nehru was drafting or polishing the statements by Bhagat Singh and his comrades.

(15) During his underground days, Bhagat Singh read world classics voraciously.

(16) Bhagat Singh worked as a member of the staff of many journals and newspapers including the Punjabi and Urdu Kirti, the Hindi daily Pratap, and Delhi-based Hindi journal Arjun between 1923-’28, prior to his arrest.

(17) Bhagat Singh’s writings in Hindi were published in Arjun, Maharati and Matwala.

(18) His essays in Kirti were published under the penname “Vidrohi” (“Rebel”), and in Pratap, “Balwant”.

(19) Bhagat Singh wrote nearly 37 sketches on the lives of revolutionaries out of total 48 in Phansi Ank (Gallows issue) of the Hindi monthly Chand (Moon) in November 1928.

(20) Many of his letters were published immediately after his execution in Lahore-based People, the Urdu journal Bande Mataram, the Hindi Bhavishya, Abhyuodey from Allahabad, Kanpur-based Pratap and Prabha, and Kolkata-based Hindu Panch.

(21) It’s not that Bhagat Singh is now-a-days identified as a Marxist or Socialist. Newspapers and journals in those days also described him in the way.

Professor Lal makes his observations based on Bhagat Sing’s language proficiency: “[A]ny task is achievable for revolutionaries once they set their mind to it – even learning a new language all by oneself.” It’s not only a hollow announcement by the aged revolutionary, the initiator and the central figure in organizing the Bhagat Singh Study Group, still active in organizing political education and spreading of it. Proletarian revolutionaries in countries repeatedly proved it. It’s evident in the imperialism organized invasions and civil war days in post-October Revolution and in the days of Second World War in Russia, in the epical Long March days in China, in the days of seizure of the French colonial army in Dien Bien Phu and the war against the US imperialism in Vietnam, and in revolutionary struggles in countries including the Telengana in India.

Chaman Lal presents 59 letters in the Reader. He claims, “the Sessions Court statements by Bhagat Singh can be compared to Fidel Castro’s statement in the July 1953 Moncada Garrison Attack trial in Havana with the apt title ‘History will absolve me’.”

The information presented in this article introducing the Reader are only a few of many Professor Chaman has gathered.

The Reader’s 35-page “Introduction” by Professor Chaman Lal is essential for readers trying to learn from Bhagat Singh as the section chronologically discusses developments related to the revolutionary’s life and political position.

Bhagat Singh, writes Chaman Lal, “was searching for ultimate ideology of human liberation from all […] oppression and exploitation, he had almost become a committed Marxist through his contacts with Kirti group of Ghadrite revolutionaries of Punjab. [….] The only difference he has with his comrades was about the programme of the revolutionary party; for Bhagat Singh and his comrades were convinced that to awaken the country from slumber, the youth need to perform daring acts of revolution and make sacrifices to advance the movement.”

Despite Bhagat Singh’s political position based on class-point of view, the revolutionary’s identity is still tarnished by a group of scholars. Historian, and Warwick University’s professor David Hardiman described Bhagat Singh and Chandrashekhar Azad – as “terrorists” during a lecture in the UK in 2014, which sparked protests by the people from this sub-continent. The historian was delivering lecture at the 24th I P Desai Memorial Lecture – “Nonviolent Resistance in India during 1915-1947” – organized by Centre for Social Studies on February 14. Hardiman said:

Terrorist groups, who predate Mahatma Gandhi, were always there alongside Gandhi’s non-violent movement.

Some of these famous figures were Bhagat Singh and Chandrashekhar Azad, who were involved in organisations like Hindustan Republic Association (HRA) and Hindustan Republic Socialist Association (HRSA).

Hardiman’s remarks against the revolutionaries angered the audience, who compelled him to clarify, following which, he said, “I did not use the word terrorists as a derogatory term.”

Major Unmesh Pandya, member of executive council of Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, who was amongst the audience, stood up during the lecture and protested against Hardiman’s remarks.

“The UK-based scholar used word terrorists seven to eight times for the revolutionaries. There is a unanimous understanding between the academicians of the entire world not to use the word terrorist for the people who had not killed innocent civilians. One can use words like extremist or revolutionary,” Pandya said.

“A terrorist means who terrorises people. But freedom fighters like Bhagat Singh or Chandrashekhar Azad initiated armed movement against imperialism. If one considers any violent or armed movement as a terror activity, then under that definition British Raj or Queen Victoria’s activities can also be defined as terrorism,” he added.

Defending Hardiman, Professor Ghanshyam Shah, a political scientist and member of the Board of Governors of Centre for Social Studies, said his remarks should be taken in a different periodical contexts.

Condemning Hardiman’s comment, human rights activists and a scholar of Bhagat Singh’s works, Hiren Gandhi termed the remarks as “logical in the context of a Britisher”.

“We believe he was a revolutionary, they (Britishers) believe he was a terrorist. That is very natural and logical for a Britisher. Bhagat Singh had done 79 days hunger strike that shows he also believed in non-violence and Satyagraha.”

Quoting from Collected works of Bhaghat Singh, Gandhi said, “To root out imperialism and its vested interests and to bring socialism, terror acts are necessary.

“Bhagat Singh believed that revolution does not mean change of power, but it also implies transformation of society. That transformation can be achieved after a long process, which includes violent and non-violent ways,” Gandhi said quoting Bhagat Singh.” (India Today, “Bhagat Singh, Azad were terrorists, says UK historian”, February 17, 2014)

The debate helped reiterate Bhagat Singh’s goal: Transformation of society.

Similarly, Chaman Lal’s book helps understand development of political ideas/theories, and of forms of struggle of a phase in this subcontinent.

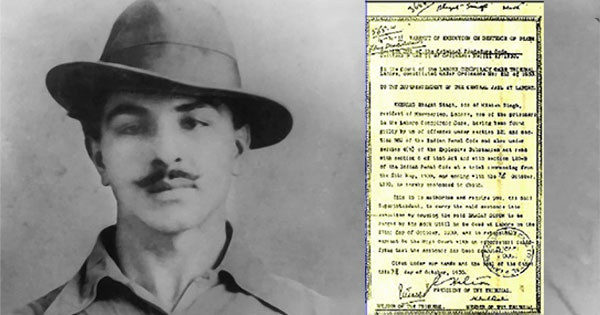

The revolutionary – Bhagat Singh – was hanged to death by the colonial British raaj on March 23, 1931 in Lahore jail, in today’s Pakistan, with his comrades Rajguru and Sukhdev. According to the V N Smith, then Superintendent of Police (political), Criminal Investigation Department, Punjab, the time of the hanging was pulled forward by the executioners: “Normally execution took place at 8 A.M., but it was decided to act at once before the public could become aware of what had happened. [….] At about 7 P.M. shouts of Inquilab Zindabad were heard from inside the jail. This was correctly interpreted as a signal that the final curtain was about to drop.” (Memoir of V N Smith, cited in The Tribune (Chandigarh, India), December 11, 2005, “Was Bhagat Singh shot dead?”) The document about the execution of death sentence of Bhagat Singh says: “I [superintendent of the jail] hereby certify that the sentence of death passed on Bhagat Singh has been duly executed and that the said Bhagat Singh was accordingly hanged by neck till he was dead at Lahore Jail on 9 pm Monday the 23rd day of March 1931. The body was not taken down until life was ascertained by a medical officer to be extinct; and that no accident, error or other misadventure occurred.” (The Economic Times (India), March 26, 2018, “Pakistan displays Bhagat Singh’s case file for the first time”) Bhagat Singh was cremated at Hussainiwala on the river Sutlej.

Bhagat Singh, the revolutionary, introduced the slogan that turned into a war cry of the exploited people in their struggle for independence in this sub-continent: Inqeelaab Zindaabaad – Long Live Revolution.

Farooque Chowdhury writes from Dhaka.

in Life/Philosophy — by Farooque Chowdhury — October 24, 2019

“Bhagat Singh”, writes Professor Chaman Lal, “was searching for the ultimate ideology of human liberation from all kinds of oppression and exploitation, he had almost become a committed Marxist through his contacts with Kirti group of Ghadrite revolutionaries of Punjab.”

Professor Chaman Lal discusses the revolutionary in the “Introduction” of his The Bhagat Singh Reader (HarperCollins Publishers India, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, 2019; henceforth Reader): “The only difference he [Bhagat Singh] has with his comrades was about the programme of the revolutionary party; for Bhagat Singh and his comrades were convinced that to awaken the country from slumber, the youth need to perform daring acts of revolution and make sacrifices to advance the movement.”

By 1928, Bhagat Singh and his comrades including Sukhdev, Bhagwati Charan Vohra, Bejoy Kumar Sinha, Shiv Verma and Jai Dev Kapoor were getting more convinced about the need of a socialist agenda for their revolutionary party. In a September 1928-meeting in Delhi, at the proposal of Bhagat Singh and seconded by Sukhdev, Bejoy Kumar Sinha, Shiv Verma and Jai Dev Kapoor, their organization was rechristened Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA). Instead of engaging with conspiratorial work Bhagat Singh, prior to the formation of the HSRA, trained himself in mass organizational work through the Naujwan Bharat Sabha (NBS). The NBS was organized in the pattern of Young Italy, an organization of the youth inspired by Mazzini and Garibaldi. By that time, the Ghadarite revolutionaries returned from the Soviet Union and set up the Hindi and Urdu journal Kirti. During their stay in the Soviet Union, the revolutionaries were trained in Communist theory at the Eastern University of the Toilers in Moscow. Bhagat Singh was a member of the editorial staff of Kirti, and worked closely with the journal. Even before organizing the NBS in Lahore, Bhagat Singh was in touch with communists in Kanpur, a city overwhelmingly populated by the working class. Bhagat Singh was literally a part of the communist movement in India since the movement’s inception. However, Bhagat Singh didn’t formally become a member of the Communist Party, which was in its formation stage. He met Muzaffar Ahmad, one of the founders of the Communist movement in India, when Muzaffar Ahmad went to Lahore. Bhagat Singh had no reservation about formally joining the Communist Party. But he was trying to shape the HSRA. (Reader, “Introduction”)

Thus, Professor Chaman Lal establishes the fact regarding Bhagat Singh: A communist revolutionary, and not relying on individualistic, conspiratorial work. His claim is supported by the following fact Chaman Lal presents in the “Introduction”: Bhagat Singh’s jail writings show he was convinced that HSRA has to organize workers, peasants, students and other potential revolutionary sections of the society in mass organizations.

However, as Professor Lal writes, Bhagat Singh and his comrades felt the need for some spectacular revolutionary action along with noble sacrifice by the young men. They thought the actions were needed to awaken the masses in upsurge against the British.

Probably, here – spectacular revolutionary action by the youth – is a point of discussion/debate on Bhagat Singh’s and his comrades’ understanding of the social process leading to mass upsurge. Pro-people revolutionary theoreticians can answer the questions/explain the problem:

What leads to mass upsurge, what powers the dynamics of people rising in revolt, and what are the tasks to be carried on to unite and awaken the masses of people so that they rise in revolt? Is it spectacular revolutionary action by the youth? Answers to the questions are to be searched in the perspective of India during Bhagat Singh’s period – a colonized, backward society, an economy with feudal connections, formation of classes including the working classes, level of class struggle, class alignment, etc.

While the HSRA was trying to focus upon organizing workers, peasants, students and youth, cases including the Saunders murder case didn’t allow it to work openly. This was a limitation imposed by reality, which the HSRA could not overcome. On the other hand, the HSRA could not work under the cover of the Congress as both of the political parties had fundamental differences. To Bhagat Singh, the only option in this “binding situation was to awaken the countrymen by their revolutionary activities, but with minimum loss of life.” (ibid.)

This type of development, mentioned by Professor Chaman Lal, is important for analyzing the development of revolutionary organization and struggle in this subcontinent. It was a path with unimaginable hurdles. The width and height of the hurdles will be perceptible if the class issue, mentioned above, and the theoretical aspects are taken into consideration. Not only this subcontinent of Bhagat Singh’s time, many lands still today are facing similar problems – how to and from where to begin, how to organize the masses of workers, peasants and sections of society with aspiration for radical change, how to overcome hurdles set up by status quo.

So, accusations like “Bhagat Singh or some-he or some-she didn’t do this or failed to do that” are easy to make; but considering the subjective and objective conditions help identify the problem or the source of the failure; and that identification will show blaming Bhagat Singh for many failures is not correct.

The “riddle”/problem turns more complex if it’s checked in comparison to the bourgeoisie or some other section/class organizing, mesmerizing, mobilizing peasantry and workers to follow the pseudo liberators – how those, to put it in a simple and broad way, profit oriented interests or compradors pulled the peasantry and workers under their banner? Millions were spellbound by those fake liberators. On the contrary, millions of people followed the Mao-led communists in China in a great retreat, and then, to wars to victory while Chiang was running campaigns, one after another, with divisions of soldiers against the communists-led forces. Those were hurdles also. Therefore, the questions are: What happens how and where? What are the, to put it simply, factors, or elements that enable to overcome hurdles created by classes inimical to the people?

Professor Chaman Lal presents a number of spectacular facts in the “Introduction” section of the Reader:

(1) The NBS helped organize Bal Bharat Sabha (BBS), an organization of school students between the ages of 12 and 16.

(2) The NBS was inspired by the sacrifice of Kartar Singh Sarabha, executed at the age of 19 in Lahore in 1915.

(3) Kahan Chand, an 11-year old student and president of BBS at Amritsar, was sentenced to three months of imprisonment for his revolutionary activities.

(4) Yash, a 10-years old activist, was persecuted on three counts including assisting the Lahore city branch of the Congress party and the NBS.

(5) In those days, 1,192 juveniles, all under the age of 15, were convicted by the mighty British raaj “civilizing” this subcontinent; and all of these children were convicted for political activities. Of these convicted children, 739 were from Bengal and around 189 were from Punjab.

(6) Bal Students Union was also active in those days.

(7) The young activists were influenced by Bhagat Singh.

Professor Chaman Lal presents a lot of information related to Bhagat Singh. These include:

(1) Bhagat Singh joined Hindi Pratap, and for about six months, Bhagat Singh wrote for Pratap under the pen name of “Balwant”.

(2) Bhagat Singh worked for flood relief.

(3) He also worked as a headmaster in a national school at Shadipur near Aligarh.

Bhagat Singh, Chaman Lal writes, “wanted to remove the terrorist tag that was attached to their organization […] For this, they wanted to use platforms from where their voice could reach millions of people.” (ibid.) Therefore, it appears that Bhagat Singh chose mass line – to the masses, among the masses.

Bhagat Singh’s life was always in danger as the British raaj considered the revolutionary as one of its boldest enemies. Referring to Shaukat Usmani’s autobiography Chaman Lal writes: During Shaukat Usmani’s visit to Moscow, Stalin asked Usmani to send Bhagat Singh to Soviet Union. “Seeing Bhagat Singh growing into a full-fledged socialist revolutionary, Jawaharlal Nehru, too, wished to send Bhagat Singh to Moscow, and was even ready to fund his trip as he told Chandra Shekhar Azad. Bhagat Singh’s uncle, Ajit Singh, had also wished Bhagat Singh to come to him in South America. But Bhagat Singh and his comrades were destined to die for the country.” (ibid.) It – destined to die for the country – was their commitment, a commitment to organize a society free from exploitation, a society humane in character, a society liberated from all backwardness and retrogressive ideas.

The first section of the Reader is a collection of letters and telegrams from Bhagat Singh. The first letter, available to the Reader, was to his paternal grandfather, Arjun Singh, on July 22, 1918 from Lahore. Bhagat Singh was staying there with his father to continue studies. About three years later, on November 14, 1921, in another letter to the grandfather, Bhagat Singh writes about a railway workers’ strike: “The railway people are planning to go on a strike these days. One hopes that it would begin immediately after next week.” The student finds an issue – workers’ strike – to mention in the letter while there were other issues that could have pulled his attention and he could have mentioned those in the letter, but the revolutionary ignored those and focused on the working people.

Bhagat Singh’s following letters show his widening political awareness. In a letter to father, Bhagat Singh writes: “My life has been dedicated to the noblest cause of attaining freedom for Hindustan. That is why worldly desires and comfort hold no attraction to me.” In the letter, written in 1923, he reminds his father: “You would remember that when I was a kid, Bapuji [paternal grandfather] had announced at the time of my yagyopavit [Hindu thread ritual] ceremony that I would be dedicated to the service of my nation. Therefore, I am fulfilling the vow taken at that time.” The young man’s commitment and truthfulness to the commitment are voiced in the letter. The youth that thus began the journey continued until sacrificing self on the altar of people’s liberation.

A few letters from his revolutionary days tell a truth:

The young revolutionary was under surveillance by the colonial rulers. During the time, Bhagat Singh was just 19 years old. But, the empire identified its enemy – Bhagat Singh. The letters written to authorities at different levels including secretary of the Punjab government show the way the revolutionary was fighting for rights. Bhagat Singh wanted, as he wrote in one of his letters, “a direct, plain and detailed reply” from the secretary of the Punjab government whether the government issued any order for intercepting his letters; and if such order was issued, an explanation – “when and why?”

Bhagat Singh, in another letter to the same bureaucrat, asserted his right: “[…] I have a right to enquire such a question relating to myself.” The question was: “[…] what led the Punjab government to issue such orders” – intercept his letters. (Letters, November 17 and 26, 1926)

The letters show a number of aspects of the person, Bhagat Singh, and the struggle against the colonial raaj, which include (1) an unrelenting character [revolutionaries are unrelenting]; (2) using every millimeter of space available to wage a struggle [matured revolutionaries use every millimeter of space]; (3) a form of struggle; (4) level of surveillance [omnipresent, still today, in bourgeois democracies]; (5) the level the empire was taking down its crushing weight to silence the people in the colony – this subcontinent; and (6) contradiction between the colonizing imperialist power – the Great Britain – and the people of this subcontinent.

The letters Professor Chaman Lal presents in the Reader tell aspects of struggle Bhagat Singh had to carry on. These, therefore, are a record of struggle of the people of this land had to wage to attain independence. Thus, inversely, these expose, to some extent, the uncivilized imperialist character a bourgeois democracy attains whenever it knifes a colony to exploit and plunder.

The issues of surveillance, uncivilized practice and non-response are part of the bourgeois-imperialist culture, in this case, political culture, and practice. It’s a practice of imperialist-bourgeois rule. It’s not a 1984 or “big brother” case, as the bourgeois sages mention citing the Orwell-novels. These sages are shameless. They don’t look into their home, but denounce others in manners blazoned with lies.

Professor Chaman Lal’s Reader, in this way, helps not only understand Bhagat Singh, but also the revolutionary’s development, time, and the colonial rule. It helps form a perspective.

A part of the perspective has been told by Lala Lajpat Rai: “If a government muzzles its people, shuts out all open avenues of political propaganda, denies them the use of firearms and otherwise stands in the way of a free agitation for political changes, it is doubtful if it can reasonably complain of secret plots and secret propaganda as distinguished from open rebellion.” (Young India, an interpretation and a history of the nationalist movement from within, “Introduction”, first published in 1916)

Another part of the perspective has been told in another way: In India, “the compromising section of [the] bourgeoisie has already managed, in the main, to strike a deal with imperialism. Fearing revolution more than it fears imperialism, and concerned more about its moneybags than about the interests of its own country, this section of the bourgeoisie, the richest and most influential section, is going over entirely to the camp of the irreconcilable enemies of the revolution, it is forming a bloc with imperialism against the workers and peasants of its own country.” (Stalin, “The Political Tasks of the University of the Peoples of the East”, speech delivered at a meeting of students

of the Communist University of the Toilers of the East, May 18, 1925, Works, vol. VII, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, erstwhile USSR, 1954)

of the Communist University of the Toilers of the East, May 18, 1925, Works, vol. VII, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, erstwhile USSR, 1954)

Bhagat Singh had to operate within this perspective, which a section of analysis ignores while evaluates the revolutionary. It’s a gross error. Professor Chaman Lal’s Reader helps cast off the error.

Note: This is the 2nd part of a series introducing The Bhagat Singh Reader by Professor Chaman Lal. The 1st part appeared in Countercurrents on September 28, 2019.

in World — by Farooque Chowdhury — November 22, 2019

“We are next to none in our love for humanity. Far from having any malice against any individual, we hold human life sacred beyond words. We are neither perpetrators of dastardly outrages, nor, therefore, a disgrace to the country […]” This was the statement by Bhagat Singh and B K Dutta in the sessions court, Delhi, on June 6, 1929. Asaf Ali read out the statement in the court on behalf of the revolutionaries facing trial.

The statement clarifies the revolutionaries’ position further as they said:

“We humbly claim to be no more than serious students of the history and conditions of our country and her aspirations. We despise hypocrisy, our practical protest was against the institution, which since its birth, has eminently helped to display not only its worthlessness but its far-reaching power for mischief.”

The revolutionaries were emphatic in making their position – love for humanity, no malice against any individual, human life sacred, not perpetrator of dastardly outrages, despise hypocrisy, protest against the institution with its far-reaching power for mischief. This statement, although known to all, needs reiteration. The need for reiteration of this position arises as to a section of today’s political activists, human life bears no value, rather, sectarian ideology values; as this section throws away humanity while practicing ideology and politics. Dastardly outrages are part of political activism of this section; and hypocrisy is one of the tools this section uses in propagating and practicing its ideology and politics. This section doesn’t aim at institutions organized and kept active to torment humanity, torture people, loot people’s resources, exploit labor, and perpetuate exploiters’ rule, which ultimately keeps the system of exploitation intact. To this section, practicing lie is their morality, as this section doesn’t look at exploitation, which uses lies to fool the exploited. Nevertheless, no noble, from class point of view, cause, no ideology and politics of people, no political movement of the exploited is possible to organize on lies and hypocrisy, by sparing institutions of exploitations, by ignoring the question of exploitation – appropriation of surplus labor. This is the reason that makes Bhagat and Dutta’s statement immemorial in history.

The statement is considered as, Professor Chaman Lal writes in his The Bhagat Singh Reader (HarperCollins Publishers India, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, 2019; henceforth Reader) one of the “classical political documents” of this subcontinent. He also considers it as one of the “most significant political statement from the Indian revolution and revolutionaries.”

However, this should be mentioned that the statement refers to ideals of many political figures including Shivaji, Kamal Pash and Lenin as equivalent; although that is not in reality. Lenin had proletarian class point of view, which is absent in some other cases. The reference to the ideals, it’s understood, was from the standpoint of spirit – attitude for defiance, struggle, and challenge – in broader terms, perhaps, and not from specific political point of view.

The revolutionaries made another statement. Both of the two statements are considered as classic political documents from this subcontinent. These documents are essential to understand the development of political thought and political struggle in this vast land spanning from the Khyber to Kohima, Manipur. These are important documents in anti-imperialist struggle, and in the struggle for liberation of the people in this wide land; because, (1) imperialism has yet to be pushed back from this land rich with resources and with strategic position, and, (2) people are not liberated from exploitation. Black sahibs have replaced white sahibs, only. In cases, situation in areas of socio-economy and politics has deteriorated if compared to a number of aspects between the two – colonial and neo-colonial – periods. The fundamental contradictions are broadly the same: between the exploited and the exploiters, between imperialism and the people.

A number of political forces ignore these contradictions as these forces don’t find contradiction in life, in society. The reason behind their failure: Identifying contradiction in life, and consequently, in economy and politics, in areas of interests. A few don’t admit the contradictions because of their ideology, which in ultimate analysis doesn’t stand for the exploited. Moreover, a part of today’s “staunchest” fighters are “fiercely” against one brand of reactionaries, one colored backward-looking forces, one type of repression; but they feel shy to look at the entire question of the exploitation and dispossession. They are scared to question the entire system of exploitation. They forget to search the root of all repression against all the exploited irrespective of color, caste and creed; and they, thus, join hands with another brand of reactionaries, with another color of sectarian and supremacist roaders, with another faction of imperialists, and, at times, shamefully, with intelligence agencies donning another cloak. Nevertheless, the crude “clever tact” gradually is exposed to political activists aware of basic questions related to contradictions in a society. That’s the reason these “fierce fighters” don’t look at the contradiction-question, but shout with questions of repressions to a single sect – an act of betrayal to the exploited people.

From this point, the documents are not only classic, but also essential learning material for today’s learners of class politics. And, here, Professor Chaman Lal has done the splendid work – present the political documents. The Reader, thus, appears an essential book for political scientists and political activists/learners.

Bhagat Singh’s call is still relevant if one looks at the reality gripped by exploitation in this land. In one of his political letters, documented in the Reader, the revolutionary writes:

“The youth will have to spread [the] revolutionary message to the far corner of the country. They have to awaken crores [10 million=1 crore] of slum-dwellers of the industrial areas and villagers living in worn-out cottages, so that we will be independent and the exploitation of man by man will become impossibility.” (Message to the Punjab students’ conference, October 19, 1929, p. 65-66)

The message was read out in the conference, chaired by Netaji Subhas Bose – a powerful political position – held on October 19, 1929 in Lahore; and it was published in the Tribune on October 22, 1929.

The message, addressed to “Comrades”, begins by telling about a significant political path – renounce adventurism. The first sentence says: “Today, we cannot ask the youth to take to pistols and bombs. Today, students are confronted with a far more important assignment. In the coming Lahore Session the Congress is to give call for a fierce fight for the independence of the country. The youth will have to bear a great burden in this difficult time in the history of the nation.” (ibid.)

The proposals – to the youth, to the Congress – reflect the reality of that time: The youth were the vanguard in political fight, or, the youth were considered in that way; and, it was the Congress that was considered as the main conveyer of the call to independence. Readers of the history of political fights, factional fights, within the Congress at different phases of the political organization are aware of the factional fights and the parties entangled in those fights. The organizers of the struggle for an exploitation-free society had to confront that reality – either make a compromise with the reality, or, ignore the reality, or, handle the contradiction-filled reality in a correct way; and all of these were tactical questions.

Bhagat Singh’s last letter written to his comrades on March 22, 1931 tells the high moral ground, sense of dignity, allegiance and duties to the people, and the revolutionary spirit he held. The revolutionary, without any hypocrisy, writes:

“It is natural that the desire to live should be in me as well, I don’t want to hide it. But I can stay alive on one condition that I don’t wish to live in imprisonment or with any binding.

“My name has become a symbol of Hindustani revolution, and the ideals and sacrifices of the revolutionary party have lifted me very high – so high that I can certainly not be higher in the condition of being alive.

“Today my weaknesses are not visible to the people. If I escape the noose, they will become evident and the symbol of revolution will be tarnished, or possible obliterated. But to go to the gallows with courage will make Hindustani mothers aspire to have children who are like Bhagat Singh and the number of those who will sacrifice their lives for the country will go up so much that it will not be possible for imperialistic powers or all the demoniac powers to contain the revolution.

“And yes, one thought occurs to me even today – that I have not been able to fulfill even one thousandth parts of the aspirations that were in my heart to do something for my country and humanity. If I could have stayed alive and free, then I may have got the opportunity to accomplish those and I would have fulfilled my desires. Apart from this, no temptation to escape the noose has ever come to me. Who can be more fortunate than me? These days, I feel very proud of myself. Now I await the final test with great eagerness. I pray that it should draw closer.”

He concluded the letter by writing:

“Your comrade

“Bhagat Singh”

The letter tells about a revolutionary, about the attitude and feeling to life, people and country revolutionaries should have. It’s a lesson to all revolutionaries, to all aspiring to serve people. And, it’s not only of that period; it’s of all periods in societies struggling for radical change, for totally altering exploiter-exploited equation – make all the exploited free from all forms of shackles. The shackles are not only of economic and political exploitation, but also of indignity and dishonor.

Bhagat Singh’s letter to B K Dutt from Central Jail in November 1930 is an example of the revolutionary’s idea and ideal:

“The judgement has been delivered. I am condemned to death. In these cells, besides myself, there are many other prisoners who are waiting to be hanged. The only prayer of these people is that somehow or other they may escape the noose. Perhaps I am the only man amongst them who is anxiously waiting for the day when I will be fortunate enough to embrace the gallows for my ideal.

“I will climb the gallows gladly and show to the world as to how bravely the revolutionaries can sacrifice themselves for the cause.

“I am condemned to death, but you are sentenced to transportation for life. You will live and, while living, you will have to show to the world that the revolutionaries not only die for their ideals but can face every calamity. Death should not be a means to escape the worldly difficulties. Those revolutionaries who have by chance escaped the gallows for the ideal but also bear the worst type of tortures in the dark dingy prison cells.”

These utterances reflect the revolutionary’s attitude to life, ideal and duty. The revolutionary, like his many comrades, was steeled in the fire of revolution.

Their struggle inside prison was exemplary, also. Bhagat Singh and his comrades, Chaman Lal writes in the Reader, carried on hunger strike for 110 days, which they began on June 15, 1929 demanding status of Political Prisoner. Jatindra Nath Das, Bhagat Singh’s comrade, died on September 13, after 63 days of hunger strike. The hunger strike was halted on October 4, 1929 after concrete assurance from the colonial British government and Congress leaders. But, the British government officials not only dishonored the commitment they made, but resorted to oppressing the revolutionaries in jail, and even in court. Bhagat Singh and many were injured after they were badly beaten by police between October 21-24 in court and in jail. That was imperialist civility and rule of law!

On February 14, 1930, hunger strike was again initiated to realize all the demands. This hunger strike was of two weeks.

These struggles are noteworthy not only in the context of this sub-continent, but also in the context of all other countries.

The Reader presents many important political documents – works of Bhagat Singh – necessary for learners of people’s politics. A number of the works point out the position proletarians should proclaim. The manifesto of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) declares:

“Revolution is a phenomenon which nature loves and without which there can be no progress either in nature or human affairs.”

It characterized the Indian capital of that time:

“Indian capital is preparing to betray the masses into the hands of foreign capitalism and receive, as a price of this betrayal, a little share of government of the country.”

The manifesto, then, presented a path:

“The hope of the proletariat is, therefore, now centered on socialism, which alone can lead to the establishment of complete independence and the removal of all social distinction and privileges.”

It called upon the youth:

“Sow the seeds of disgust and hatred against British imperialism […]”

The political document, at its conclusion, declared:

“The sovereignty of the proletariat […]”

The document is an example of the ideological position, orientation and worldview the HSRA held: For the exploited, for a society free from exploitation, oppose all exploiters including imperialism.

Chaman Lal writes in the Reader: “Two documents – the manifestos of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha (NBS) and the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) – are the most important ideological texts to understand Bhagat Singh and his comrades’ struggle for Indian freedom from British colonialism. The drafts of both were written by Bhagwati Charan Vohra, with Bhagat Singh being consulted before they were finalized for publication.”

Studying Bhagat Singh is essential for the study of politics, both of the people and of the ruling elites, in this subcontinent. The Reader helps this study by presenting a lot of basic documents. Its appendices, if someone ignores rest of the volume, presents many facts documents and information required primarily for study of Bhagat Singh. The Reader, in its 616 pages, bears the hard labor Professor Chaman Lal has put to present Bhagat Singh. And, Bhagat Singh is neither a single revolutionary nor representing a single revolutionary organization oriented to proletarian ideal. Bhagat Singh represented a people’s revolutionary aspiration, dream and political struggle in a historical period. The Reader, thus, is an important resource material to begin study of that struggle in that period, which is required for study of the present.

Note: This is the 3rd/concluding part of a series introducing The Bhagat Singh Reader by Professor Chaman Lal. The 1st and 2nd parts appeared in Countercurrents, India, Frontier, Kolkata, India, and New Age, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Farooque Chowdhury writes from Dhaka.

No comments:

Post a Comment