Book Review: Bhagat Singh – The ‘Lamp of Reason’ That ‘Ceased to Burn’

There has hardly been a time when books or other publications on Bhagat Singh were not being written. This began in 1929 when publications on Bhagat Singh became the target of British colonial proscriptions. By now more than 600 books have appeared on Bhagat Singh in nearly 20 Indian and foreign languages. While many books are based on romantic tales of his life, few books focus on his ideas and role in the Indian freedom struggle. Amar Kant Jttu's book, Walking With Bhagat Singh Soon After Independence, is one such book that focuses on his revolutionary ideas and interprets his thoughts in the Marxist tradition.

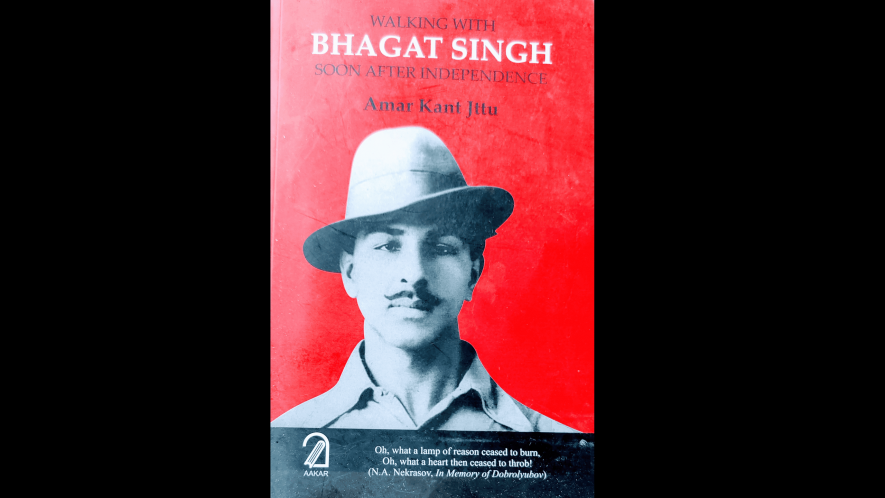

The book was published just before the onset of COVID in 2019. The cover has a handsome hat-wearing photograph of Bhagat Singh, and what attracts the attention of the reader, is a couplet from a poem by Russian poet NA Nekrasov written in memory of Dobrolyubov, the pre-socialist revolution Russian materialist philosopher who died almost at the same age as Bhagat Singh, at 24 years.

The couplet is:

Oh, what a lamp of reason ceased to burn,

Oh, what a heart then ceased to throb!

This is not only a most appropriate poetic manner of describing Bhagat Singh’s personality, it also brings to mind Friedrich Engels’s tribute to Karl Marx at the time of his burial in London, that "the greatest living thinker ceased to think!"

That the writer Amar Kant Jttu, a retired public relations officer of the Punjab government, wrote this book at the age of 90+ years shows what a magical effect Bhagat Singh has on people; that age is no bar from getting inspired by his personality. Perhaps, it is the other way round, it inspires people to stay young at least mentally, if not physically, as he is ever a young icon of the revolution. The only other such icon is Che Guevara.

Apart from his mother, father, and grandfather, the author has dedicated the book to the revolutionaries fighting for the establishment of ‘scientific socialism in the world!’ The dedication itself shows the expectations of the author, which are idealist in present circumstances.

The book is divided into 40 small chapters but begins with a short piece from ‘The Roll of Honour’, published long ago by Kali Charan Ghosh, a directory of Indian revolutionaries. Its title is 'Glorious Deeds or Revolutionaries: The Salt of History'. Further, there is Bhagat Singh’s March 20 1931 letter to the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab with the title ‘The War Shall Continue'. Then come acknowledgments in which the author expresses his gratitude to authors like Howard Zinn and Eduardo Galeano whose writings like The Peoples History of the United States and Open Veins of Latin America inspired him to write this book. He is also inspired by authors like Suniti Kumar Ghosh, Rajni Palme Dutt, and Ashok Mitra, and their books and Monthly Review journals.

Before his ‘Introduction’, the author has included four short prefaces by his kin and friends, which perhaps is a sort of thanksgiving for supporting or fulfilling his desire of writing this book at a late age.

In his introduction to the book, Jttu has claimed that this book is an effort to critically analyse the three most popular icons of the freedom struggle of India-- Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Bhagat Singh -- from the prism of revolutionaries. The author thinks all three to be geniuses but opines that Gandhi and Nehru are superabundantly glorified, whereas Bhagat Singh has not been given his due. The author has taken up the task to undo this imbalance and put Bhagat Singh as a more important figure than these two icons. He has also referred to some earlier books like those of Manmathnath Gupta and Hans Raj Rehbar. He clearly states in his introduction that Bhagat Singh’s ideology was Scientific Socialism. In the next 40 chapters, Jttu tries to prove his point.

In the very first chapter - 'Tracking down Bhagat Singh and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru' -- Jttu comes down rather heavily on the ‘duplicity’ of Nehru, when he refers to him as General Secretary of Congress in 1929 and publishes Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt’s June 6 Court statement in the sessions court of Delhi in ‘The Congress Bulletin’, which was widely appreciated. Incidentally, this statement in full was carried by every major daily of that time and one paper, Pioneer, even carried a version, some parts of which were objected to and not taken on record by the sessions judge concerned.

Mahatma Gandhi objected to its publication in the Congress bulletin and as per Jttu, Nehru apologised: "I am sorry you disapproved of my giving Bhagat Singh and Dutt’s statement in the Congress Bulletin. I was a little doubtful as to whether I should give it, but when I found there was a very general appreciation of it among Congress circles, I decided to give extracts. It was difficult, however, to pick and choose and gradually most of it went in. But I agree with you that it was somewhat out of place. I think you are mistaken that the statement was the work of their counsel (Asaf Ali). My information is that the council had nothing or practically nothing to do with it. He might have touched the punctuation. I think the statement was undoubtedly a genuine thing."

Apart from the description of it as the ‘duplicity’ of Nehru, it is interesting that well-known historian VN Datta in his book ‘Gandhi and Bhagat Singh’ has described this statement to be authored by Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru himself has gone with the version of Asaf Ali when the sessions judge had questioned accused Bhagat Singh and Dutt’s competence in English to pen down such statement, to which Asaf Ali had responded what Nehru had quoted that "I may have touched upon punctuation here and there, but I had submitted what my clients had handed me over to this court’. Asaf Ali wrote this in his memoir later about this case.

Jttu has described in this statement and later on in the same case to the High Court in appeal in July 1929, as "phenomenal brilliance of Bhagat Singh."

Incidentally, Bhagat Singh, in both the Delhi Assembly bomb case and the Lahore Conspiracy case, had chosen to argue his case and accepted only legal counsel to help prepare his defence. Asaf Ali represented BK Dutt in legal terms in the High Court and was only a legal counsel to Bhagat Singh, who did not agree with Asaf Ali's approach of denying the act of revolutionaries to defend themselves legally.

Bhagat Singh later objected to Asaf Ali’s arguments in defence of Hari Kishan, contesting Asaf Ali denying the revolutionary act of Hari Kishan to save him. Bhagat Singh, in his two letters from Lahore Jail, one of which was even ‘lost’ (as Bhagat Singh himself referred to his ‘lost’ letter in the second letter), emphasised owning up to the revolutionary act and asserting the reasons for the act. (This author edited The Bhagat Singh Reader, pages 78-85, Harper Collins India). It is also a fact that most, rather all of the statements on behalf of Dutt or other revolutionaries from Lahore jail were drafted by Bhagat Singh, some of these statements are available in Bhagat Singh’s own recognised handwriting.

Jttu refers to Nehru’s An Autobiography ,first published in 1936, where on pages-174-76, Nehru discusses their amazing popularity as "he became a symbol to vindicate the honour of Lala Lajpat Rai and through him of the nation". Jttu later refers to Nehru’s ‘Glimpses of World History’, in which he refers to Karl Marx and Lenin, but not Bhagat Singh and Indian revolutionaries in world history.

As per Jttu, Gandhi began his political life in India in 1915 as a British loyalist. He quotes Gandhi himself to buttress his argument. He quotes for the April 25, 1915 dinner speech at Madras, in which Gandhi pledged loyalty to the British empire. The source of this speech is the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi volume 13, pages 59-60. For enlisting into the army to fight in World War 1, Gandhi was awarded the title of ‘Kaiser-e-Hind'.

As per Jttu, the poor Indian recruits were used as ‘cannon fodder’ in the service of the British empire. He claims that before the Kaiser-e-Hind medal, Gandhi was also awarded Boer and Zulu medals during his South African stay. The author claims that Gandhi did not return these medals as Rabindranath Tagore had renounced his knighthood in protest against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919.

Perhaps Jttu’s claim is unverified. Gandhi did return his Kaiser-e- Hind medal in 1920 during the non-cooperation movement and in support of the Khilafat movement, but Sarojini Naidu, also the recipient of the Kaiser –e-Hind medal returned her medal in protest against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, like Tagore did.

The author is very critical of Gandhi, especially his support to the British colonial regime in suppressing Garhwali Rifles led by Chandra Singh Garhwali, who had refused to fire at peaceful protesters of the 1930 non-cooperation movement at Peshawar and the 1946 Royal Indian Navy revolt.

Jttu also described the March 5, 1931 Gandhi-Irwin Pact, which did not take into account the release or commutation of the death sentence of revolutionaries and only sought the release of Congress party protestors as ‘Surrender Pact’. Nehru himself had described the irony of the situation that ‘when talks will be held with British rulers--the dead bodies of Bhagat Singh revolutionaries will be staring us’ (Not exact words, but the spirit of phrase).

Jttu acknowledges in a whole chapter devoted to the issue –‘Was Mahatma Gandhi duty bound to save Bhagat Singh? And that Mahatma Gandhi did take up the issue of execution of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev many times with Lord Irwin, but Jttu’s grouse is that he was never very serious about it.

Both Bhagat Singh and Gandhi had different political perspectives and it is unfair to say, as people generally say, that Gandhi was powerful enough to save Bhagat Singh’s life. The British colonial regime was determined to hang Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev through a sham trial, as it feared the Bolshevik socialist perspective gaining ground in case Bhagat Singh was allowed to live. Probably, Gandhi faltered in not asserting his principled moral position of being anti-capital punishment, for Bhagat Singh or anyone else.

In several chapters author, Jttu narrates the factual story of Naujawan Bharat Sabha and Hindustan Socialist Republican Association/Army (HSRA), the organisations created by Bhagat Singh along with his other comrades, which are the strength of the book. The story of the Simon Commission, the killing of Lala Lajpat Rai, the assassination of Saunders, bombs in Central Assembly, Delhi, subsequent trials and court statements of Bhagat Singh, epoch-making hunger strikes in jail, and fearlessly kissing the gallows-- have all been described factually but with passion.

The conclusion of the author is in the chapter titled ‘Bhagat Singh was True Marxist’. In support of his conclusion, Jttu has included some of the major ideological writings of Bhagat Singh such as ‘Letter to Young Political Workers’, 'Court Statements', 'Why I am an Atheist', and March 20, 1931 letter to Lieutenant Governor Punjab- 'The War Shall Continue' -- and an ample number of quotations from ‘Jail Notebook’ as well as from other writings.

While everyone may not agree with the arguments of Jttu, especially about Gandhi and Nehru, it goes to the author's credit that he directly quotes Gandhi and Nehru to build his arguments. His interpretation can be contested based on some other writings of Gandhi and Nehru, but the author cannot be blamed for misquoting them. He had, after all, in the beginning, accepted Gandhi, Nehru, and Bhagat Singh - -all three as geniuses. For Jttu, Bhagat Singh was a bigger genius than the other too. One can disagree with him, but he has the right to have his opinion.

Jttu, Amar Kant, Walking with Bhagat Singh: Soon after Independence, Delhi, Aakar Books, 2019, Pages 320, Rs 595.

The author is Former Dean, Faculty of Languages, Panjab University Chandigarh and Honorary Advisor, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre.

No comments:

Post a Comment