What three letters, part of the Lahore Conspiracy Case, will be part of an updated Bhagat Singh Reader?

As India completes 75 years, the discovery of three petition letters will enrich the history of its most charismatic revolutionary.

August 13, 2022 1:14:36 pm

An artist’s impression of Bhagat Singh. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)

An artist’s impression of Bhagat Singh. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)The completion of 75 years of Independence is a good time to recall Bhagat Singh, the iconic hero of India’s freedom struggle who has been frequently invoked by political parties of late, although often without sufficient knowledge of — and respect for — his true revolutionary ideals.

The last time the great personalities of the Independence Movement were celebrated at a scale somewhat approximating the current one was in 2007, the year in which five national anniversaries were observed — 150 years each of the First War of Independence and the birth of Lokmanya Tilak; 60 years of Independence; and 75 years of the death and 100 years of the birth of Bhagat Singh.

The Manmohan Singh government formed national committees with leaders of all opposition parties including the BJP, a large number of programmes were held at the national and state levels and a range of publications appeared between 2006 and 2008.

SUBSCRIBER ONLY STORIES

Earlier, in 1997, when IK Gujral was the prime minister, the golden jubilee of Independence was celebrated with great solemnity but limited noise. The focus in 1997 was on Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Subhas Chandra Bose, while in 2007, greater attention devolved on Tilak and Bhagat Singh. In 2022, the spotlight remains on Bhagat Singh, and he shares it with Sardar Patel, Birsa Munda, and Dr BR Ambedkar.

In 2007, the government’s Publications Division commissioned me to prepare a volume of the writings of Bhagat Singh, which was published in Hindi with a translation in Urdu. The Hindi original was updated in 2020 and published in four volumes.

In 2019, I edited The Bhagat Singh Reader, a collection of all his writings that could be located until 2018. Singh wrote in English, Hindi, Urdu and Punjabi, though he was also well versed in Sanskrit and Bengali, and was learning Persian in jail. Of the 133 writings in The Reader, 58 are in English and 46 in Hindi. Since then, I have come across three more important documents — a letter by Singh to the Special Magistrate, Lahore Conspiracy case, published in The Hindustan Times on February 13, 1930, in which he laid down the reasons for his refusal to come to court, and two hitherto unseen letters in his own hand, part of the Lahore Conspiracy case files. Both petitions protest the fact that he’d been refused legal counsel, and that hurdles had been put on his attempts to communicate with the court. These new writings will be part of forthcoming updated edition of The Bhagat Singh Reader likely to come out later this year.

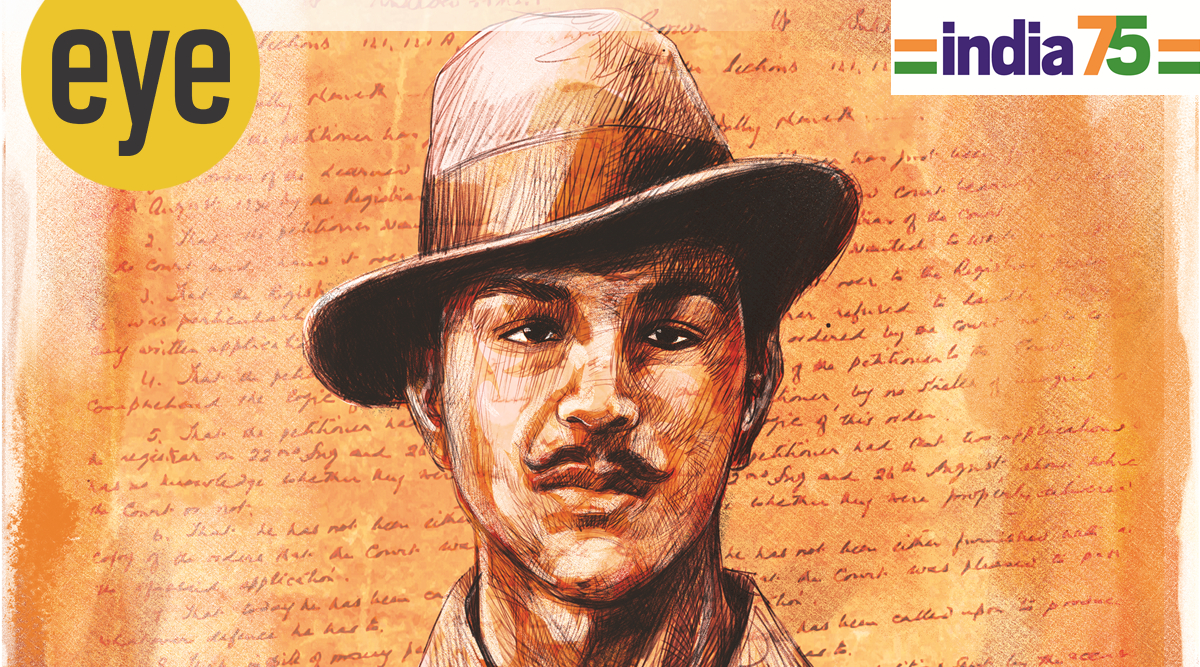

Starving to death for country’s honor. (Credit: Photograph by Ramnath/ Courtesy Chaman Lal, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, New Delhi)

Starving to death for country’s honor. (Credit: Photograph by Ramnath/ Courtesy Chaman Lal, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, New Delhi)A summary of the short, remarkable life of Bhagat Singh, and the context in which these three letters were written, would be in order. Singh was arrested twice and faced two trials in his 23-year life. He was first arrested on May 29, 1927, and kept in police custody until July 4, 1927, during which he was brutally tortured to extract a confession. He was given bail against Rs 60,000, a very large sum in those days, and the case was withdrawn after it was hotly debated in the Punjab Assembly.

He was arrested for the second time on April 8, 1929, at the Central Assembly in Delhi, the present Parliament House, which had been inaugurated two years earlier. Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt offered themselves for arrest after throwing bombs at the Assembly. Both were convicted on June 12 and were transferred to Mianwali and Lahore jails, respectively, on June 14. During the journey, they went on a hunger strike that ended after 110 days on October 4. Their comrade Jatin Das, who too was on a hunger strike, died on September 13, 1929.

Proceedings in the Lahore Conspiracy case, the second case Singh faced, began on July 10, 1929. On a hunger strike at the time, Singh was brought to court in Lahore from Mianwali jail on a stretcher. Singh, Dutt and some other revolutionaries went on a hunger strike again on February 4, 1930, as the colonial administration refused to honour their commitments.

The letter published in The Hindustan Times was accompanied by the news of the hunger strikes by the revolutionaries. The two handwritten letters are from the last days of the trial by the Special Tribunal, comprising three High Court judges. Its proceedings began on May 5, 1930, and the verdict was announced on October 7. The date of execution was fixed for October 27, 1930, a few days before the term of the Tribunal was scheduled to end. Following an appeal and its rejection, Bhagat Singh was hanged on March 23, 1931, along with comrades Rajguru and Sukhdev.

Chaman Lal is honorary advisor, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, Delhi Archives, New Delhi, and India’s foremost scholar on Bhagat Singh.

Letter 1

Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt’s letter to the special magistrate in the Lahore Conspiracy case, which was published in The Hindustan Times, dated February 13, 1930, giving reasons for their refusal to go to court — being “harassed ceaselessly”, “plea for interviews” with them were rejected, the “defence counsel not being allowed to attend court”, the “lack of supply of newspapers to literate undertrials” such as themselves. (CREDIT: Courtesy Chaman Lal, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, New Delhi)

Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt’s letter to the special magistrate in the Lahore Conspiracy case, which was published in The Hindustan Times, dated February 13, 1930, giving reasons for their refusal to go to court — being “harassed ceaselessly”, “plea for interviews” with them were rejected, the “defence counsel not being allowed to attend court”, the “lack of supply of newspapers to literate undertrials” such as themselves. (CREDIT: Courtesy Chaman Lal, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, New Delhi)Reasons for refusing to come to court: ‘Harassed Ceaselessly’

Lahore accused’s letter to Special Magistrate

Lahore, February 10

Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt have sent the following [letter] to the Special Magistrate, Lahore Conspiracy case, Lahore through the Superintendent, Central Jail, Lahore:

In view of your statement and order dated February 4, 1930, published in the Civil and Military Gazette bearing the date of February 6, we feel it necessary to make a statement clearing the position of the accused as regarding their refusal to come to your court so that any sort of misunderstanding and misrepresentation may not be possible.

Harassed Ceaselessly

In the first place we should point out that we have not so far boycotted all the British courts. We are attending the court of Mr. Lewis who is trying us under Section 52 of Prisons Act for the occurrence of January 29 in your court. But there are special circumstances which force us to take this step-in connection with the Lahore conspiracy case. We have been feeling from the very beginning that the nonfessant attitude of the court, and misfeasance and malfeasance of the jail or other authorities, we are being harassed ceaselessly, but deliberately with a view to hamper our defense. Many of our grievances had been placed before you in a bail application, a few days back, but while rejecting that petition on some legal grounds, you did not feel the necessity of even making a mention of the grievances of the accused, on the ground of which a prayer for the bail was made.

Magistrate’s Foremost Duty

We feel that the first and foremost duty of the Magistrate is to keep his attitude quite impartial up and above both the prosecution and defence parties. Even the Hon’ble Justice Ford gave the ruling that day, telling the Magistrate 1o be ever at arm’s length from the prosecution. The second most important thing that a Magistrate ought to keep before him is to see if the accused have genuine difficulty in connection with their defense and remove if any. Otherwise, the whole trial is reduced to a farce. But the contrary has been the conduct of the Magistrate in such an important case where 18 young men are being tried for serious offences such as murder, dacoity and conspiracy for which they may, very likely to be sentenced to death.

The main grounds on which we were forced to attend your court were the following:

The majority of the accused belong to distant provinces and all are middle class people. In these circumstances it is very difficult, nay almost impossible for their relatives to come here every now and then to help them in their defence. They wanted to hold interviews with some of their friends whom they could entrust with the reasonability of their defence. Even common sense says that they are entitled to these interviews. In this court repeated requests were made to that effect, but one and all requests went unheard.

No Interviews Allowed

Mr. BK Dutt belongs to Bengal and Mr. Kanwal Nath Tiwari to Behar. Both of them wanted to interview their friends- Shrimati Kumari Lajjawati and Shrimati Parvati Devi (daughter of Lala Lajpat Rai-editor), respectively. But the court forwarded all their applications to the jail authorities, who in turn rejected them on the plea that interviews could be allowed to relatives and counsel only. Again, and again the matter was brought to your notice, but no step was taken to enable the accused to make the necessary arrangements for their defense. Even after they had appointed their friends as their attorneys and the attorney power had been attested to by this very court, no interview was allowed to them. And the magistrate even refused to write to the jail authorities that the accused demanded the interviews for defence purposes in connection with the case which he himself was trying. And the accused, thus handicapped, could not even move the higher court. But the trial was being proceeded with. In these circumstances, the accused felt quite — helpless and for them the trial had no other value than a mere farcical show. It is noteworthy that those, and a majority of the accused were going unrepresented.

Accused’s Grievances

I am an unrepresented accused and could not afford to engage a whole-time counsel to represent me throughout the lengthy trial. I wanted his legal advice on certain points. And at a certain stage I wanted him to watch the proceedings personally to be in a better position to form his opinion. But he was refused even a seat in the body of the court. Was this not a deliberate move on the part of the authorities concerned to harass us to hamper our defence Counsel from attending the courts to watch the interests of their clients, who are not present nor even represented by them. What are the “Special circumstances of this case”, that forced the Magistrate to adopt such a rude attitude towards a barrister…, thus discouraging any counsel might be invited to come to assist the accused? What was the justification in allowing Mr. Amar Das to occupy the chair of defence when he is no longer representing any party and not even giving any legal advice to any person? I was to discuss with my legal adviser the question of interviews with attorneys and to instruct him to move the High Court on this point. But I could not get the opportunity to discuss it with him at all and nothing could be done. What does this all amount to? Is it not throwing dust into the eyes of the public by showing that the trial is being held quite judicially? The accused did not absolutely get any opportunity to make any arrangements for their defence. This is what we protest against. If there is to be no fair play, there need not be a show. We cannot see injustice being done in the name of justice. In these circumstances we all thought it fit that either we should have a fair chance of defending ourselves or be prepared to bear the sentence passed against us in a trial held in our absence.

The third main grievance is about the supply of newspapers. The undertrials as such should not be treated as convicts and only such restrictions can be justifiably imposed upon them as may be extremely necessary for their safe custody. Nothing beyond that can be justified. The accused who cannot be released on bail should never be subjected to such hardships which may amount to punishment. Hence every literate undertrial is entitled to get at least one standard daily newspaper. The “Executive” agreed on certain principles to give us one daily English newspaper in the court. But things done by half worse than not done at all: Our repeated requests asking for a vernacular paper for the non-English reading accused proved to be futile. We had been returning The Tribune daily in protest against the order refusing a vernacular paper.

Any how these were the three main ground, an which we announced on January 29 about our refusal to come to the court.

As soon as these grievances would be removed, we will ourselves quite willingly come to attend the court — Free Press (News agency).

Inside the three-column news, a special box titled “Lahore Hunger Strike: Prisoners Look Pulled Down”, dated February 10, mentions: The effects of the hunger strike are becoming clearly marked in the case of the accused in the Lahore Conspiracy Case. When they were produced before the Additional District Magistrate, who is trying them under Section 52 of the Prisons Act, for disobedience, they looked greatly pulled down. Four of them were unable to sit in chairs and had to be stretched on mattresses in the courtroom. API news agency

(The Hindustan Times, February 13, 1930; edited excerpts)

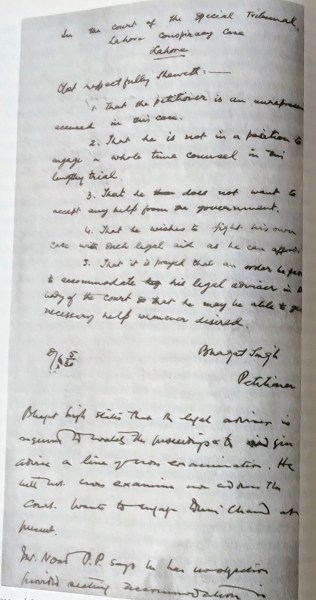

Letter 2

Bhagat Singh’s petition dated 6 May 1930, pleading that “he is not in a position to engage whole time counsel”, “that he does not want to accept any help from the government”, and that “an order be passed to accommodate his legal adviser in a body of the court.” (CREDIT: Courtesy Chaman Lal, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, New Delhi)

Bhagat Singh’s petition dated 6 May 1930, pleading that “he is not in a position to engage whole time counsel”, “that he does not want to accept any help from the government”, and that “an order be passed to accommodate his legal adviser in a body of the court.” (CREDIT: Courtesy Chaman Lal, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, New Delhi)Bhagat Singh petition for legal advisor, May 6, 1930

In the court of the special Tribunal,

Lahore Conspiracy Case

Lahore

Most respectfully Shweth,

1. That the petitioner is an unrepresented accused in this case

2. That he is not in a position to engage whole time council in this lengthy trial

3. That he does not want to accept any help from the government

4. That he wishes to fight his own case with such legal aid as he can afford

5. That it is prayed that an order be passed to accommodate to his legal adviser in a body of the court so that he may be able to give necessary help whenever desired

Bhagat Singh

Petitioner

May 6, 1930

Letter 3

Bhagat Singh’s petition dated 27 August 1930, protesting the refusal of the court registrar to accept from him an application to the court; the lack of information on whether his two earlier applications had been delivered to the court; and that even though he has been asked to produce his defence, he has not been allowed interviews to co-accused and relatives, which are very essential to the purposes of his defence. (CREDIT: Courtesy Chaman Lal, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, New Delhi)

Bhagat Singh’s petition dated 27 August 1930, protesting the refusal of the court registrar to accept from him an application to the court; the lack of information on whether his two earlier applications had been delivered to the court; and that even though he has been asked to produce his defence, he has not been allowed interviews to co-accused and relatives, which are very essential to the purposes of his defence. (CREDIT: Courtesy Chaman Lal, Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, New Delhi)Bhagat Singh petition of August 27, 1930

In the court of the special Tribunal

Lahore Conspiracy Case, Lahore

Crown Vs. Sukhdev

Charged under sections 120, 121-A, 120-B etc., IPC

Most respectfully Shweth,

1. That the petitioner has just been furnished in copy of the over of the learned courts, bearing the date August 22, 1930, by the Registrar of the Count

2. That the petitioner wanted to write an application to the court and hand it over to the Registrar personally

3. That the Registrar refused to handle it saying he was particularly ordered by the court not to accept any written application the petitioner to the Court

4. That the petitioner, by no stretch of imagination, comprehends the logic of this order

5. That the petitioner had put two applications the registrar on August 22 and 26 about which he has no knowledge whether they were properly delivered the Court or not

6. That he has not been either furnished with copy of the orders that the Court was pleased to pass in the aforesaid application

7. That today he has been called upon to produce whatever defence he has to

8. That in spite of many petitions sent by the petitioner to the learned court, no orders have been issued by court to the jail authorities to allow the interviews to co accused and relatives, which are very essential to the defence purposes

9. That it is prayed that court be pleased to inform the petitioner what order has the court been able to pass on his applications mentioned in the last paragraph. kindly pass orders intimating the petitioner to hold interviews with his relatives, thus enabling to prepare and produce his defence, which he cannot otherwise, and thirdly to stay the further proceedings of the court until the said interviews are held and proper defence are provided to him, and lastly inform the petitioner so whatever order the Court pleased to pass on this petition

Bhagat Singh

August 27, 1930

Petitioner

Central Jail, Lahore

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.