Relook at a Book: The Bolivian Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara; Che – A Memoir by Fidel Castro

The Bolivian Diaries-authorised edition, Ernesto Che Guevara, Introduction by Fidel Castro, Preface by Camilo Guevara, 1st ed. 2006, Ocean Press, Melbourne-New York, Pages 303, Indian price, Rs. 450

As one of the most important books of world revolutionary movements, this book is made up Che Guevara’s diary notes during his Bolivia mission. Beginning November 7, 1966, the diary has regular entries for 11 months, till October 7, 1967.

The next day, on October 8, 1967, Guevara was captured by the Bolivian army. He was murdered in cold blood on October 9.

Except for Cuba and its leader, Fidel Castro, and the world’s revolutionary movements, no bourgeois politician of the world expressed any sorrow or condemnation for the cruel treatment of a wounded Che and his murder at the behest of US imperialists and their lackey, Bolivian dictator Barrientos.

Che Guevara was at his marvellous best even during his one-day custody, bearing all the pain heroically and challenging his killers to shoot him.

Though the diary is not important in terms of any theoretical foundations, but it reveals, in a matter of fact manner, how selflessly and heroically Che Guevara led this most difficult mission of making revolution in Bolivia. How, despite his serious asthma problem, he left Cuba at a time when he was providing leadership in building socialism as Castro’s most trusted comrade; and how he worked in Bolivia, where most of the circumstances were hostile and conditions not favourable to advance the revolution.

But Che was Che, he could not agree to Fidel’s assessment to wait for more favourable circumstances and ground preparation before he could join the forces there. And Castro was equally great, and kept his word to allow Che to leave the Cuban government and let him organise a Cuba-like revolution in the rest of Latin American countries, a dream nurtured by Simon Bolivar to create a revolutionary United States of South America.

Che wished to begin in his motherland, Argentina, but the conditions were not yet ripe there to lead such a movement. Bolivia was also not ripe yet, but the Cuban victory was a source of inspiration.

In Cuba, the struggle had started with just 82 men on Granma, of which just 15-16 people survived. Yet, within two years, the 80,000-strong army of dictator Batista was defeated and the revolution was victorious on January 1, 1959.

Fidel Castro not only relieved Che to lead the revolution in Bolivia but he also provided men and arms, including many senior communist party cadres, who sacrificed their lives in the Bolivian mission, like Che.

The Bolivian Diaries has been edited meticulously. Apart from entries by Che, it includes rare photographs of that period, the editor’s brief note, maps of the area, including guerrilla zones, a glossary of people and terms/events, and five communiqués issued by the National Liberation Army (ELN) of Bolivia, fighting under the leadership of Che. The actual diary entries are covered in about 220 pages. A life sketch of Che is also there.

Camilo Guevara, the eldest son of Che Guevara, has written a brief but moving preface. He observes that in the last entry on October 7, 1967, “there is not the slightest tone of discouragement, pessimism, or defeatism; on the contrary, these words seem to be a beginning, a prologue...”

Camilo is sure that the enemies could have never captured Che, despite his wounded leg, broken rifle and no other weapon, except that he could not leave his other sick and wounded companeros. Camilo describes the scene on October 9 as well, when Che was murdered as the ‘order to murder him came from Washington’.

He beautifully concludes that –“Without a trial, without a thought, the new man Che Guevara represented is killed. But what is born is a yearning for the new human being, who is neither an illusion nor a fantasy. A dream, dormant for many centuries takes shape: an ethical, virtuous selfless human being. This time stripped of all myth and mysticism; this person must be fundamentally human”.

Fidel Castro wrote an Introduction to the diary in 1968, when it was published for the first time in Spanish in Havana, and two lakh copies were circulated free to Cubans. In this introduction, Fidel narrates the story of acquiring the diary from the interior minister of Bolivia, who lost his job for this, and establishing its authenticity.

The Introduction underlines the intense human character of Che and his immense bravery, it also exposes the brutalities of the Bolivian regime, which was a lackey of US imperialism and was playing a puppet’s role.

Castro also exposes the treachery of Mario Monje, secretary of the Bolivian Communist Party at that time, who ditched Che. Even the other group led by Oscar Zamora became a venomous critic of Che Guevara. Moises Guevara, the miners’ leader, joined the movement and sacrificed his life. Other comrades of Monje, like Inti and Coco Perado, also joined and proved their bravery, but Monje went to the extent of sabotaging the movement.

Che knew many peasants in Bolivia but was suspicious and cautious of their character. Despite so many difficulties, he and his comrades performed marvellous feats and the Bolivian army could succeed only on September 26, 1967 against Che’s detachment, after which this group could never overcome the damage.

Castro opines that never in history has so small a number of men set out for such a gigantic task. He has also highlighted the bravery of Che in fighting his last battle on October 8, trying to save two comrades and fighting on, even while he was wounded.

In La Paz, dictator Barrientos and defence chief Ovando decided to murder the captured Che. It was Che, who said firmly to his killer—‘Shoot! Don’t be afraid’. Still, the drunk killer could only shoot him in the side. Che’s agony in the last few hours of his life was very bitter, and Castro puts it aptly: “No person was better prepared than Che to be put to such a test”.

Castro reveals that Che’s diary was obtained without any payment and was published simultaneously in France, Italy, Germany, the US; and in Chile and Mexico in Spanish. He concludes with the famous slogan of Che- Hasta la victoria siempre! (Ever Onward to Victory).

The 25-page-long glossary gives details of almost all the people involved in this epic struggle on both sides. The first appendix refers to instructions to urban cadres, dated January 22, 1967, written by Che and Loyola Guzman, when she visited Che on January 26. According to this document’s reference, the National Liberation Army (ELN) was established in March 1967.

Che has given detailed instructions regarding all organisational aspects for the army, like supplies, finances, transport, and contact with sympathisers, etc. Other communiqués make it clear that ELN is the only responsible party for the armed struggle. In one entry, Che makes an impassioned plea to join ELN, as ‘we are restructuring the worker-peasant alliance that was broken by an anti-plebeian demagoguery.’ He is confident at this moment that ‘we are converting defeat into triumph.’

The actual diary begins on November 7, 1966, with the inspiring first sentence: “Today begins a new phase...”. The diary has an interesting entry on November 12: “My hair is growing, although very sparsely, and the grey hair are turning blond, and beginning to disappear; my beard is returning. In a few months I will be myself again.”

Che had entered Bolivia with a fake passport and he had shaved off his characteristic beard. He could not be recognised even by Castro and other comrades in Havana. Che also refers to the existence of 12 insurgents on November 27. He made it a point to write a review of each month’s events at the end of the month. November’s analysis records Che’s opinion: “Everything has gone well; my arrival was without incident and half of the troops have arrived, also without incident...”.

On December 12, Che made certain appointments in the group, giving charge to various people. On December 31, an important meeting with Monje took place. Some understanding was reached, which was not followed by Monje later.

On January 6, Che noted: “The importance of study is indispensable for the future”. In the analysis of the month, he notes with anguish: “As I expected, Monje’s position was at first evasive and then treacherous”. He notes with concern that the party (communist party) has taken up arms against us...” Che concluded ironically: “Of everything that was envisioned, the slowest has been the incorporation of Bolivian Combatants.”

February was not a very conducive month for the group. They had been walking ‘miles and miles’.

On March 14, Che noted: “We heard parts of Fidel’s speech in which he makes blunt criticism of Venezuelan communists and harshly attacks the position of Soviet Union on Latin American puppets.” On March 17, he notes another loss for revolutionaries, as many crucial weapons on backpacks were lost in crossing a river.

On March 23-24, they make gains, they capture weapons from the enemy and kill and arrest many. There is mention of French leftist Regis Debray visiting ELN. In the March 25 meeting of the group, the liberation army is given the name of National Liberation Army of the Bolivia, ELN in short.

Che notes in a detailed analysis of events in March: “The phase of consolidation and purging of the guerrilla force - fully completed”. He noted that the enemy was totally ineffective so far and he was trying to moblise peasants to isolate them.

In April, Che notes ‘total disaster’ on the 4th and ‘great tension’ on the 6th. April 11 records the radio news of a ‘new and bloody encounter’ with mention of nine dead from the army and four guerrillas. April 22 is noted for ‘making mistakes’, and 25th as a ‘bad day’ with the best guerrilla Rolando dying in ambush. The summary of April confirmed the death of Rubio and Rolando as a ‘severe blow’. The certainty of North America’s heavy intervention, which has already sent helicopters and Green Berets, is mentioned, but Che notes the morale of combatants as good.

May Day is celebrated by clearing vegetation in the guerrilla camp. The diary noted Debray’s status as a journalist being rejected by dictator Barrientos, and his trial. The summary of May is worrisome -- Che notes total loss of contact with Manila (Cuba), La Paz and Joaquin (the other guerrilla group) of ELN, reducing the strength of the group to 25; complete failure to recruit peasants, though they now admire ELN. He notes that it is a slow and patient task.

In June, the 14th is mentioned as the birthday of Che’s youngest daughter, Celia, which is his own birthday as well, which he notes simply as: “I turned 39 (today) and am inevitably approaching the age when I need to consider my future as guerrilla, but for now I am still ‘in one piece’”.

Che notes on June 23 that ‘asthma is becoming a serious problem for me and there is very little medicine left’. In the ensuing days, it worsens. On June 29, he noted they were now 24 men. On 30th, Che notes that ‘Debray apparently talked more than was necessary’. In an analysis of the month, Che notes the total lack of contact, continued lack of peasant recruitment, lack of contact with the Bolivian communist party, Debray’s case and Che’s recognition as ‘the leader of the movement’. Che notes the urgent task of recruiting at least 50 to 100 men in the movement.

The very first day of July mentions Bolivian dictator Barrientos’s press conference terming the guerrillas as ‘rats and snakes’ and calling for wiping out Che Guevara and punishing Debray. Che’s deteriorating asthma is noted repeatedly.

On July 14, Che noted with concern that the Bolivian “government is disintegrating rapidly. Such a pity that we do not have 100 more men right now.” On July 31, he wrote: “We are 22 men with two wounded, and me with full blown asthma”. The month’s analysis notes the total loss of contact continuing, lack of peasant recruitment continuing, guerrilla force becoming legendary, and the morale and combat experience of guerrilla force increasing with each battle.

On August 2, Che noted: “My asthma is hitting me very hard and I have used up my last anti- asthmatic injection, all I have left are tablets for about ten days.’ On August 8, he makes a speech to his comrades and mentions the difficult situation, but noted: “This is one of those moments when great decisions have to be made, this type of struggle gives us the opportunity to become revolutionaries, the highest form of human species, and it also allows us to emerge fully as men.....”

August’s summary mentions the blow from loss of all the documents, medicines, loss of two men, one desertion (first one). The other features of the month remain the same, but the morale factor changes to ‘decline’, though Che hopes it to be ‘temporary’.

September has much worse news as, after much confusion, it is confirmed that Tania has been killed. Mentioning 10th as a bad day, Che made a funny entry: “I forgot to mark an event: Today I took a bath after more than six months. This constitutes a record that several others are already approaching.” His 26th entry begins with the word ‘Defeat’, on 28th, the entry begins with the words ‘Day of anguish’.

The month’s summary is sad. Che now accepted: “We must consider Jouquin’s group wiped out, still hoping the report to be ‘exaggerated’ and ‘small group wandering around”. He mentions the bitter fact that the army is now more effective and peasants are becoming ‘informers’. Che underlines the most important task as ‘to escape and seek more favourable areas; then focus on contacts, despite the fact that our urban network in La Paz is in shambles, where we also have been hit hard.”

The entry on October 3 is ironic: capture of two guerrillas, Antonio (Leo) and Orlando (Camba), both betray and give information. Debray is praised for his courageous stand in the trial. The last entry on October 7 begins as: “The 11 month anniversary of our establishment as guerrilla force passed in bucolic mood with no complications”. Che mentions that ‘the 17 of us set out under a slither of a moon, the march was exhausting, no nearby houses”.

Che’s last lines: "The army issued an odd report about the presence of 250 men in Serrano to block the escape of the 37 (guerrillas) that are said to be surrounded. Our refuge is supposedly between the Acero and Oro rivers. The report seems to be diversionary. Altitude=2000 meters”.

The Bolivian Diary of Che Guevara records the 11- month glorious struggle to liberate Bolivia from the crutches of dictator Barrientos and its brutal army working directly under US imperialists.

I took look at The Motorcycle Diaries and The Bolivian Diary of Che Guevara together, though the two diaries are entirely different in content and style, one can understand his marvellous and heroic character, which made him an icon of the international revolutionary movement in every part of the world. Wherever resistance movements have erupted after Che’s murder in 1967, his photographs/posters/souvenirs have been the most visible part of demonstrations/processions etc.

Che is an icon for the youth. One can see this from the conduct of Che’s life. The Bolivian Diary shows how selfless and caring he was toward his comrades. How, despite his horrible asthmatic conditions, he suffered all the hardships of guerrilla life, walking 15-20 km a day, performing all the duties of a guerrilla, always full of optimism, even when things were going completely beyond control.

Che realistically analysed the weaknesses of the movement through his diary. He was an idealist, despite being a Marxist. Conditions were not ripe for him to go to Bolivia, which was the opinion of Fidel Castro also, but he was restless to go.

Che Guevara and Bhagat Singh-like personalities create role models for youth or struggling people by their complete selfless conduct. Che was probably hoping to create another Cuba with his 25 men or so, as in Cuba just 15-16 of them mobilised the whole of Cuba and defeated Batista.

But Che underestimated the US's role after the Cuban revolution. It would not allow another Cuba in Latin America at any cost and that is what it did in Bolivia by killing Che and many Cuban revolutionaries in 1967. Yet, the saga of Che Guevara’s bravery and struggle has become a legend and inspiration for the liberation of humankind from all kinds of oppression.

Che could have been impulsive in Bolivia, but his sacrifice created a much more powerful Che for US imperialism, which can never be killed with bullets as it has become idea-personified. The life of Bhagat Singh, an icon in South Asia, has similar characteristics.

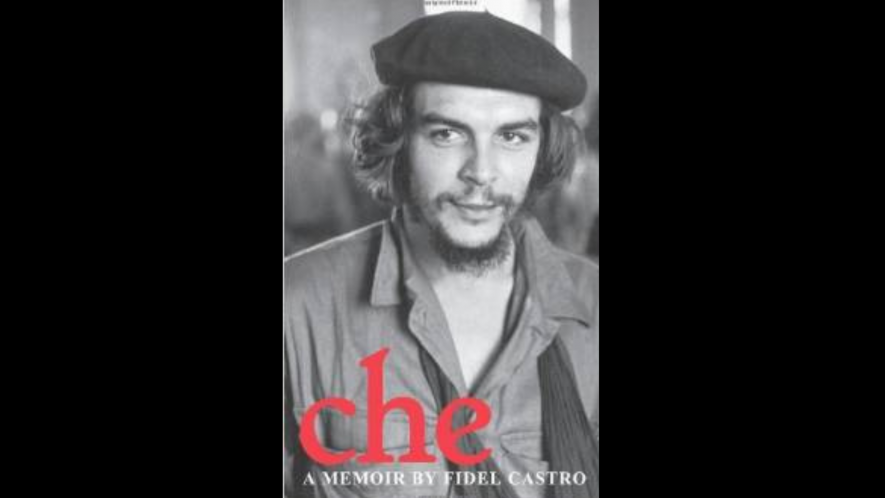

Che Guevara in the eyes of Fidel Castro

Che: A Memoir – by Fidel Castro, edited by David Deutschmann, Preface by Jesus Montane, National Book Agency, Calcutta, first Indian ed. 1994 [Original Ocean Press, Melbourne]. Rs. 100; Pages 168.

I read for the second time, and it was worth reading again. It has life sketches of both Che Guevara and Fidel Castro in the beginning, followed by Che’s life’s chronology. After a preface by Jesus Montane Oropesa, there is an introduction by David. Then, in seven chapters, Castro’s writings or lectures relating to Che Guevara have been compiled, followed by a Post Script and a Glossary of persons and events.

It starts with Che Guevara’s farewell letter to Castro before proceeding to start revolutionary activities in Africa and Latin America. As Che was not seen in Havana, all kinds of rumours and scandals were spread by the bourgeois media and Castro made the letter public only when Che reached Bolivia in 1966 to participate in the armed struggle that finally led to his life being sacrificed in 1967.

Then there is a speech by Castro on Cuban television on October 15, 1967 to announce the death of Comrade Che. The third chapter includes his speech in front of a million people in Revolutionary Plaza, Havana, in a memorial meeting for Che. Chapter four includes Castro’s introduction to the Bolivian diaries of Che, which were published in 1968 after these were recovered from Bolivia.

Chapter five includes Castro’s speech in Chile, where he inaugurated the first statue of Che Guevara. Chapter six is Castro’s interview with Italian journalist Gianni Mina on the occasion of 20th anniversary of Che’s martyrdom in 1987 and the seventh and last chapter includes Castro’s speech on that occasion at electronic factory named after Ernesto Che Guevara in the city of Pinar del Rio.

It is difficult to take notes on this book - I may have to copy almost half of it. Suffice it to say that it is a very important book to understand both Che and Fidel. It confirms my earlier conviction that Che and Bhagat Singh have much in common. What has been aptly described by Castro in the context of Che is largely applicable to the personality of Bhagat Singh.

Chaman Lal is retired Professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and Honorary Advisor to Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre New Delhi. He can be contacted at prof.chaman@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment